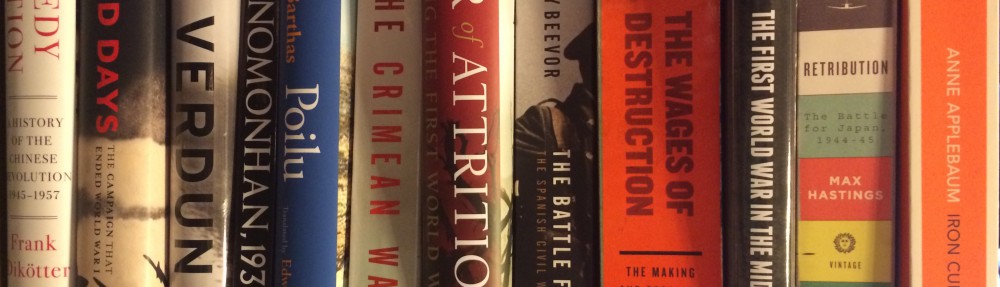

Yesterday’s post on my favorite WWI books reminded me about another piece of diplomatic history I read in summer 2011: Ernest R. May’s Strange Victory. It’s a great account of just how, against everyone’s expectations—including the Wermacht generalship—Germany was able to conquer France in such a short time in 1940. There’s a frustratingly weak nod towards political science analysis at the end, largely based on personalities, but when the book is at its best, it’s (a) doing the hard work of figuring out exactly what happened (a contribution of history as a discipline that I think we tend to underestimate) and (b) essentially describing the equilibrium to a Colonel Blotto game.

Who’s this Colonel Blotto? Most game theorists will recognize the problem we represent with the good Colonel: he’s got to allocate limited defensive assets across a mountain and a pass, while his opponent has to choose between attacking either the mountain or the pass. (Let’s set aside, for now, the whole “why you might attack a mountain” question; this ain’t about geography.) The problem, of course, is that Colonel Blotto’s opponent would like to attack at the location the Colonel doesn’t defend, while he’d of course like to defend the point of attack. If the enemy knew the Colonel’s position, he’d attack elsewhere, and if the Colonel knew the enemy’s plans, he’d defend accordingly. The solution to such a game, with apologies to precisely how we might interpret mixed strategies, is to obscure your intentions—which the Nazis were, for the most part, able to do. The French, of course, fortified their eastern frontier with Germany, anticipating an attack along that axis (ha!), but the German plan, as we know, sent the materially and technologically inferior (at the time) Wermacht through BeNeLux and conquered France in a matter of weeks—all because they won the Blotto game.

It’s a long read, but—trust me—totally worth it.