After a break to take the second exam last Thursday (a break in which I forgot to do a “let’s look back” filler piece), we spend some time today on the Eastern Front, which—if I’m being honest—I’ve short-shrifted a bit in the course thus far. That’s too bad, because I think we can use the Eastern Front to learn a lot about the reasons behind the consuming indecisiveness of the war’s early years…on both fronts.

Last week, we showed why military technology and the strategic environment produced an attritional equilibrium on the Western Front, where each side sought to return to mobile warfare but was unable to do so without opening up its own lines to the breach that the opponent’s (similar) strategy denied it. The end result, of course, was a long period in which a military decision was impossible. Two factors often put up to explain the lack of decision on the battlefield are (a) the compactness of the Western Front, where ratios of soldiers per mile were always higher than the East, and (b) a lack of “imagination” amongst each side’s commanders—that is, the lack of an appropriate strategy. However, in class today we show that neither of these is a terribly strong explanation for the lack of decision, because the Eastern Front was, while much longer and less densely-manned and home to a wider variety of tactical combinations, almost equally indecisive.

The Eastern Front was never as deeply entrenched or as static as the Western, meaning that the fighting was certainly more mobile; commanders had the room in which to maneuver their troops, and whether or not we call it incompetence, we saw a variety of attempts to break the stalemate that the belligerents on the Western front didn’t have available. Nonetheless, with cities changing hands back and forth in both East Prussia and Galicia, as well as Russian Poland, the reality of modern firepower and the limits of logistics in newly-captured territories ensured that, as in the West, no local successes could be converted into a genuine, sustained breakthrough—that is, into a more general success.

Thus, even though it wasn’t as static as the Western Front, the war in the East was still one of reserves, indecision, and grignotage—of attrition, albeit with a different face. Only when reserves and populations were used up, pulled out of the line by collapse or by exhaustion (or, you know, the Bolshevik Revolution), did the character of the war in the East change. Years later, with the wearing-down of German reserves in the face of Allied weight of numbers, similar factors would presage the end of the war in the West…the length of the front or “imaginations” of the generals notwithstanding.*

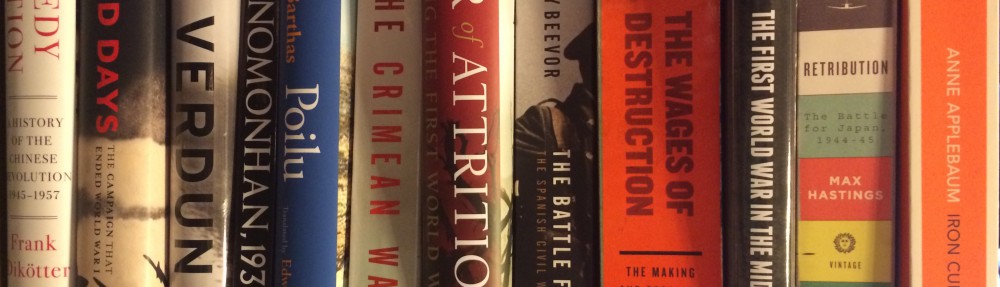

* For one of the best accounts of the similarities on Eastern and Western Fronts, check out William Philpott’s War of Attrition. It’s excellent.